but when you come from water

Water is Life.

A rallying cry of Indigenous Peoples, and a plain and simple fact. But what exactly does it mean to come from water? In her poem Atlas, where this exhibition draws its title from, Terisa Siagatonu ponders the realities of being from Sāmoa, an island in the South Pacific, very often overlooked on maps, and that is victim to colonization, tourism, and American military imperialism. For Siagatonu, water is the place she is from, in part because it threatens to overtake what little land makes up Sāmoa, but also because the ocean’s vastness is easier to see than the island.

As water surrounds her homelands, how might water shape other places we are from? From the Navajo Nation to sub-Saharan Africa to California, water scarcity, the lack of running water, and drought make everyday tasks and health a challenge. On the other hand, abundance of water, like post-Hurricane Katrina or the Kiribati Islands threaten to swallow the very existence of a physical space. In both instances of too little or too much water, water structures our homes, physical and mental health, and lives.

In The Chapter House’s inaugural online exhibition but when you come from water, artists contributed works that consider water as a material, medium, inspiration, and something to fight for. This exhibition is specifically inspired by the work of Emma Robbins, The Chapter House’s Founder and Executive Director of the Navajo Water Project. but when you come from water explores interpretations of water in artistic form from artists from across the world.

If you open up any atlas

and take a look at a map of the world,

almost every single one of them

slices the Pacific Ocean in half.

Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater on World Map (‘English Navy’ and ‘Aqua’)

Meg Arsenovic

2019

Acrylic on World Map

This map has been painted over to highlight the location of the meteor strike and resulting impact crater which ultimately formed the Chesapeake Bay. This ‘impact event’ shaped the intricate waterways where Indigenous Peoples thrived for thousands of years while also creating the gateway for British settlers to enter the land that would become the United States.

Land of Water II

Edwige Charlot

Scanned Wax Print on Paper

11.25" x 17.75"

Manatee at Sea

Pat Guizzetti

2021

Acrylic on canvas

48" x 36"

To the human eye,

every map centers all the land masses on Earth

creating the illusion

that water can handle the butchering

and be pushed to the edges

of the world.

As if the Pacific Ocean isn’t the largest body

living today, beating the loudest heart,

the reason why land has a pulse in the first place.

San Juan River

Colleen Cooley

Digital photograph

Her journey begins,

From the San Juan mountains,

Taking you through canyons and washes,

Across the deserted landscape,

Carrying snow melt,

Making you shiver,

She is sacred to many,

Providing water to plenty,

She is full of silt and mud,

But, her journey continues,

As she flows into the Colorado River

But When You Come From Water… You Make Life Grow

Crystal Dugi

Procreate digital piece

On the reservation water is literally Life. It helps crops grow and thus sustains all life.

But When You Come From Water, Rain Drops Don't Just Fall

Illustrated piece by Crystal Dugi

Poem by Tami Dugi

The audacity one must have to create a visual so

violent as to assume that no one comes

from water so no one will care

what you do with it

and yet,

people came from land,

are still coming from land,

and look what was done to them.

Poceta de memoria (Well of memory)

Victoria Ravelo

Photocopy wheat pasted on reclaimed wood

“A photo of my mother’s hometown in Cuba sits on a piece of reclaimed wood in Philadelphia. She tells me that many children loved to swim in la pocetas (tide pools) near the ruins of what once was a Greek-revival style mansion.”

Mounds

Alec Rovensky

2020

Clay

Clay is intrinsically tied to water, which transports, forms and resists the material. With the withdrawal of moisture, the residual matter maintains its shape but exhibits properties opposite to those of its wet state, becoming brittle and weak. Upon firing, the clay enters its strongest phase. Mounds is a representation of the delicate cycle of clay and its relationship to water.

Across Oceans

Nicole Godreau Soria

Acrylic, Relief, Handmade Paper, Metal Leaf on Reclaimed Wood

“Across Oceans explores diasporic foodways, ancestral memory, and time travel through alchemy. This piece pays homage to the known and unknown women who passed down this ritual of cooking plantain to me across oceans and generations.”

When people ask me where I’m from,

they don’t believe me when I say water.

So instead, I tell them that home is a machete

and that I belong to places

that don’t belong to themselves anymore —

Mất Nước / To Lose Water, To Lose Homeland

Ennïs Tô

2017

Analog collage

“Nước is the Vietnamese word for water. But it is also the word for homeland and by extension—country. In the Vietnamese language, when you ask someone where they are from, you are asking which water they are from. In the words of translator Huỳnh Sanh Thông, nước as 'water' is the concept of people who have gathered near a body of water to grow rice for one another, establish a stable community, who share rain and drought, plenty and famine, peace and war together. This collage is an ode to the stories of Vietnamese refugees such as my family whose stories began far before they stepped foot onto this land. We live and embody water spontaneously and instinctively, unconscious to the ancestral origins of this double meaning. Nước is a reminder that our relationship to water has been paramount to our collective identity in a time before imperialism, the construction of borders, war, and displacement.”

Bridge Chair

Hannah Wong

2020

Wood, yarn, thread

“Bridge Chair represents the tumultuous feelings I have when reflecting on my first homes: Hanoi, Vietnam and the so called Sacramento, California (USA). Hanoi has had a stronghold in my identity, but there is often a fear of crossing the emotional and physical barriers that lie in between the U.S. and Vietnam. I have not been back to Hanoi for a long time, but I have found identity in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta where I have been raised most of my life and was surprised to recently learn of the deltas and bridges in Hanoi. Bridge chair reflects on this connection and how water has given life to both of my communities, but has also been a metaphorical symbol for forces that compel me to places I may not intend to inhabit, but are part of my life.”

Waiting on a Līhau Rain

grave markers.

Kiaʻi no kōna puʻuwai.

Līhau:

swift moving, sudden,

as the heavens huli.

Rain droplets cling

to her salt-lined face,

hold tight to numb-filled lash;

each a prayer, kūpuna-sent.

persist.

Wet clothes cling

to fevered frame.

The rise and fall

of weighted chest,

off-beat with her

slowing pulse.

She takes another

shaky breath,

surprised she hasn't

flatlined yet.

— broken and butchered places that have made me

a hyphen of a woman:

a Samoan-American that carries the weight of both

colonizer and colonized,

both blade and blood.

California stolen.

Samoa sliced in half stolen.

California, nestled on the western coast of the most powerful

country on this planet.

Samoa, an island so microscopic on a map, it’s no wonder

people doubt its existence.

California, a state of emergency away from having the drought

rid it of all its water.

Samoa, a state of emergency away from becoming a saltwater cemetery

if the sea level doesn’t stop rising.

LA River Paper

Emma Robbins

2018

Naturally occurring paper (algae, leaves, bird materials), thread

14 x 11 in

LA River Paper is made of foraged material, meticulously stitched together, from the Los Angeles River one of the treaty pieces included in Robbins' series Tseebííts'áadah, a collection of works about the Eighteen Lost Treaties of California.

Continuation

Photographs

Well Wisher

Blue McRight

2012

Mixed media

Well Wisher consists of a tree standing upside down on its cut branches, which appear as dry roots studded with nozzles. Wrapped with black bandages and thread and topped by a rusted, archaic water pump, Well Wisher is a fool’s device that promises water but pumps only dry air.

My mama in another world swimming with the sharks

James Vallie

2021

When people ask me where I’m from,

what they want is to hear me speak of land,

what they want is to know where I go once I leave here,

the privilege that comes with assuming that home

is just a destination, and not the panic.

Water Shadow

Amruta BP

Wood burning

Storm Collection 5

Margalena Lepore

Oil on canvas

Splash

Reenie Charriére

2016

Made of rainwater and plastic shards collected from waterways all over the world, held in Ziploc bags and sewn together. This is one of the water columns the artist has created. The pieces get reused for other sculptures.

—Not the constant migration that the panic gives birth to.

What is it like? To know that home is something

that’s waiting for you to return to it?

Rainbow Over The Canals

Joel Bull

35 mm Film Photograph

When the rain stops, we sometimes see a beautiful rainbow that fascinates us and shows us the power of water.

The Cup of Water and Life

Ryan Dodson

Sterling silver cup. Handmade bezel. Hand stamped

2” x 3”

This cup is the embodiment of water within our universe. With water held inside the cup the addition of the Sun, the Stars, and the moon, this cup holds all that is sacred for us together in a continuous circular design. The cup has no beginning and no end like our universe. Each of us have a responsibility to fill our own cups so we can thrive in the big universe.

Water is Life

Chip Thomas

Photograph

Aguas Negras

Documentary film

What does it mean to belong to something that isn’t sinking?

What does it mean to belong to what is causing the flood?

So many of us come from water

but when you come from water

no one believes you.

Uewa

Kimberly Robertson

Seed beads, cedar berries and fire-polished beads on mixed-media collage, 5” x 10”

"Uewa" celebrates the survivance and re-emergence of Mvskoke knowledges and practices even under the conditions of genocide and displacement. European settlers called us Creek Indians—and later, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation—because of our proximity to water. Our original homelands were along the rivers and creeks in the Southeastern United States. Even after our forced removal to Indian Territory in the 1830s, we settled along the waterways. My people lived beside water because water is considered our first medicine. Without water, there is no life. Living in Los Angeles on unceded Tongva and Tataviam lands, away from original Mvskoke homelands and our contemporary homelands in Oklahoma, "Uewa" serves as an articulation and affirmation of Mvskoke identities, practices, and knowledges that transcend colonially-imposed borders. It speaks to my identity as a "water person," the sacred connection I have had with bodies of water since I was a young child, and the ways in which the Pacific Ocean has become an(other) mother that offers me the comfort and teachings of my ancestors.

Undark

Untitled

Dezmond Applin

Procreate digital piece

Colonization keeps laughing.

Global warming is grinning

at all your grief.

How you mourn the loss of a home

that isn’t even gone yet.

That no one believes you’re from.

Lake I

Ben Murray

2020

Acrylic on muslin

“Lake I” is inspired from Hollis Frampton's 1974 short film, "Winter Solstice", that captures the innerworkings of U.S. Steel as well as our current view of Lake Michigan where U.S. Steel sits on the coastline and lights the water.

Worried to Death

Ryan Richey

2015

Oil on canvas

16" x 18"

"I occasionally get ocular migraines, which manifest themselves in my vision as multi-colored outlines of my eyes. I use the eye shapes in my paintings as a visual motif to indicate worry. In this painting the shapes hover above where I’m from, the Midwest. I lived in and around the Great Lakes for 14 years. My time in the Midwest gave me a deep appreciation for the water and the environment. I made this painting in 2015. Since then, my dedication to protecting the environment, particularly our bodies of water, has only increased."

Ride the Wave

Alima Catellacci

Linoleum cut reduction

“This piece was inspired by the 2011 Fukushima Nuclear crisis. I saw the impact and problems that exist due to human negligence of our environment. I spend a lot of time surfing and being outside and this wave was one I spent a lot of time riding. I imagined what it would be like if drilling and environmental waste was located next to this wave. The contrast of something beautiful against something ugly is what the image attempts to capture.”

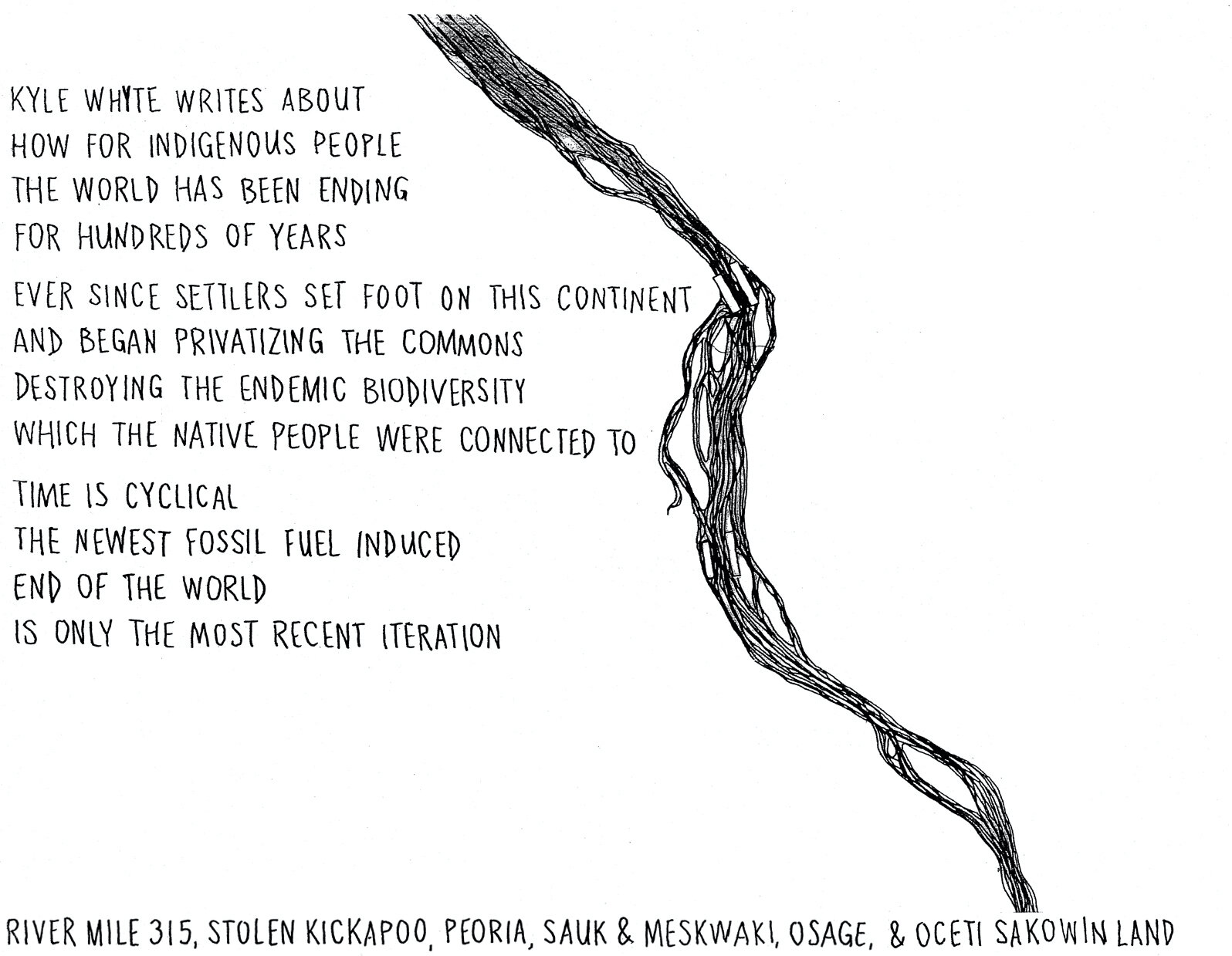

The River Herself (Kansas River at Deep Creek)

Lynn Benson

2018

Oil and acrylic on canvas

30” x 30”

How everyone is beginning

to hear more about your island

but only in the context of

vacations and honeymoons,

football and military life,

exotic women exotic fruit exotic beaches

but never asks about the rest of its body.

Where the Wildflowers Grow

Corinne Webster

2021

Mixed media on fabric

We’re water people

Ciara Khan

Digital photograph

“These photos are from a series I’m exploring called Recreation Reclamation, where I create imagery with people who have not had opportunities to deeply connect with the land around them. These photos feature my friend that has lived in Miami all her life. She has Bahamian lineage and often jokes about how she can’t swim. In these photos I’ve captured her connecting with water in Big Cypress, 729,000 acres of a freshwater swamp ecosystem. 20+ years of being in Miami and she barely knew it existed. I thought about what it is to be a Black woman and access this space safely. Recreation in South Florida is dominated by White males (sometimes armed) that have access to gear, space and permission. We walked through a trail, submerged in freshwater and eventually found a spot to rest. We sat in silence for a while breathing fresh air and noticing all the wildflowers around us. Eventually my friend broke the silence, ‘I know I can’t swim but I told you, we’re water people. I’m supposed to be here.’”

Father’s Day performance with yucca flowers

Rica Maestas

Archival pigment prints and wood (performance documentation)

20” x 14”

“This piece meditates on the aftermath of the Pueblo Revolt, wherein residents of land now called New Mexico attempted to cleanse their bodies, food, and culture of the colonizer. Reperformed in 2020 during ongoing genocide of people of color through medical neglect, economic oppression, and police brutality, this action was a grieving ritual, an attempt at atonement for my own moments of Latin fragility, and an acknowledgement of the endless effort involved in purging colonial mindsets from the body.”

#TsiiyéełPowered

Natani Notah

2017

Photo documentation of ongoing walking performance

Impermanence

Nupur Behera

2018

A cyclone was easing its way into my homeland, a series of small coastal villages across eastern India.

Making touchdown at any moment, I sat,

far away on the Pacific coast, painting with tea and watercolor,

removed by distance, the winds creeping up my spine.

I scrolled, the news drowned by the uprisings, the pandemic, the calls for justice and humanity.

I swirled in its abyss.

Water destroys as much as it renews.

It governs my people's culture, livelihood, and spirituality.

Which pieces of us would it touch this time?

The water.

The islands breathing in it.

The reason why they’re sinking.

No one visualizes islands in the Pacific

as actually being there.

Adorned Wave

beneath early afternoon sun,

pearls of the oysters residing

in the crude sands below

until grace shone undeniable,

beauty taking form anew

with every churning second

even as their crest arched

beneath the march of time

their passing noticed only by

waves who crashed just before and

those who rose in their shadow,

surely some gulls had swooped above

and crustaceans had clambered below

and fish had raced in their wake, but

none had shared a glance nor

lent pause to their quiet neighbor,

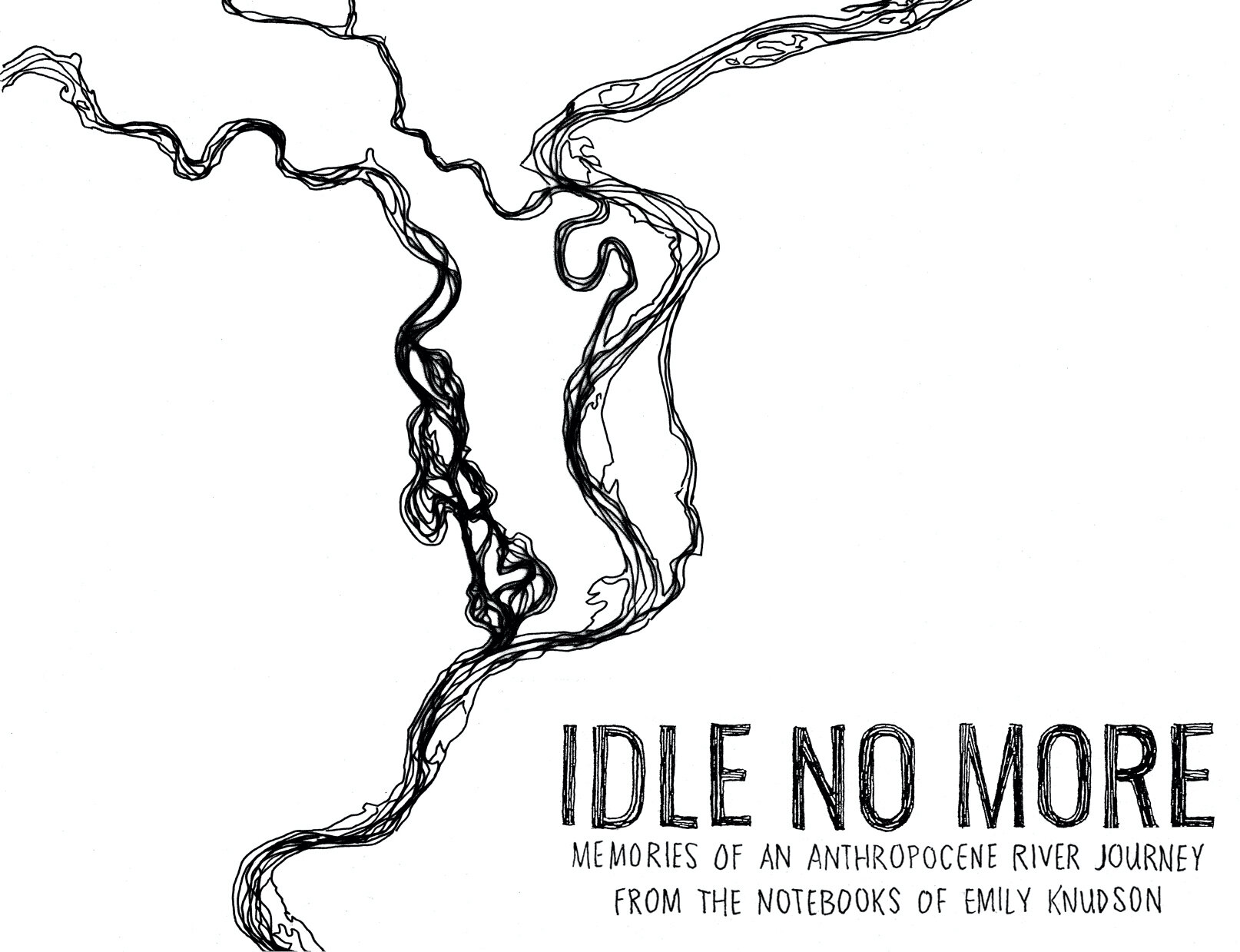

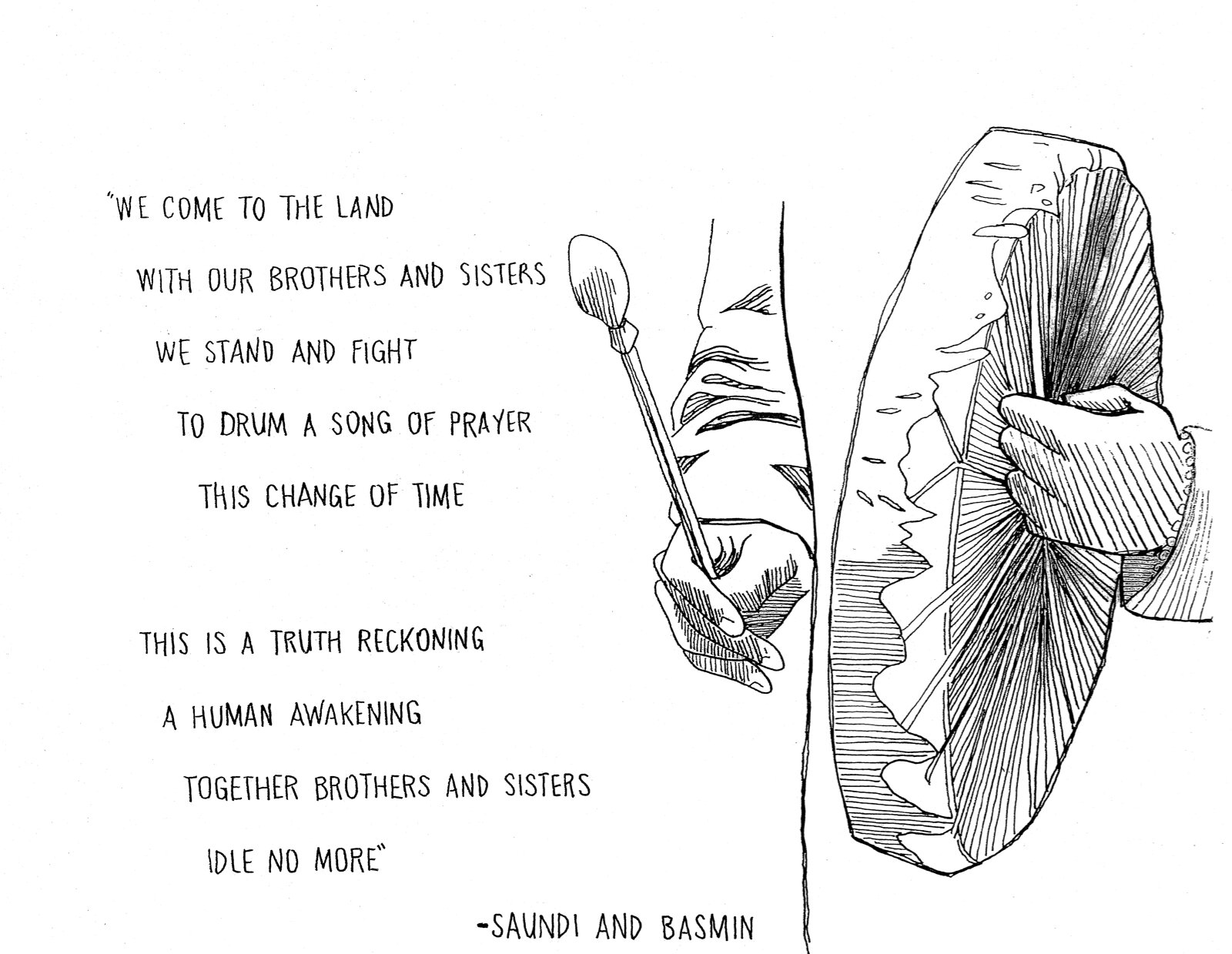

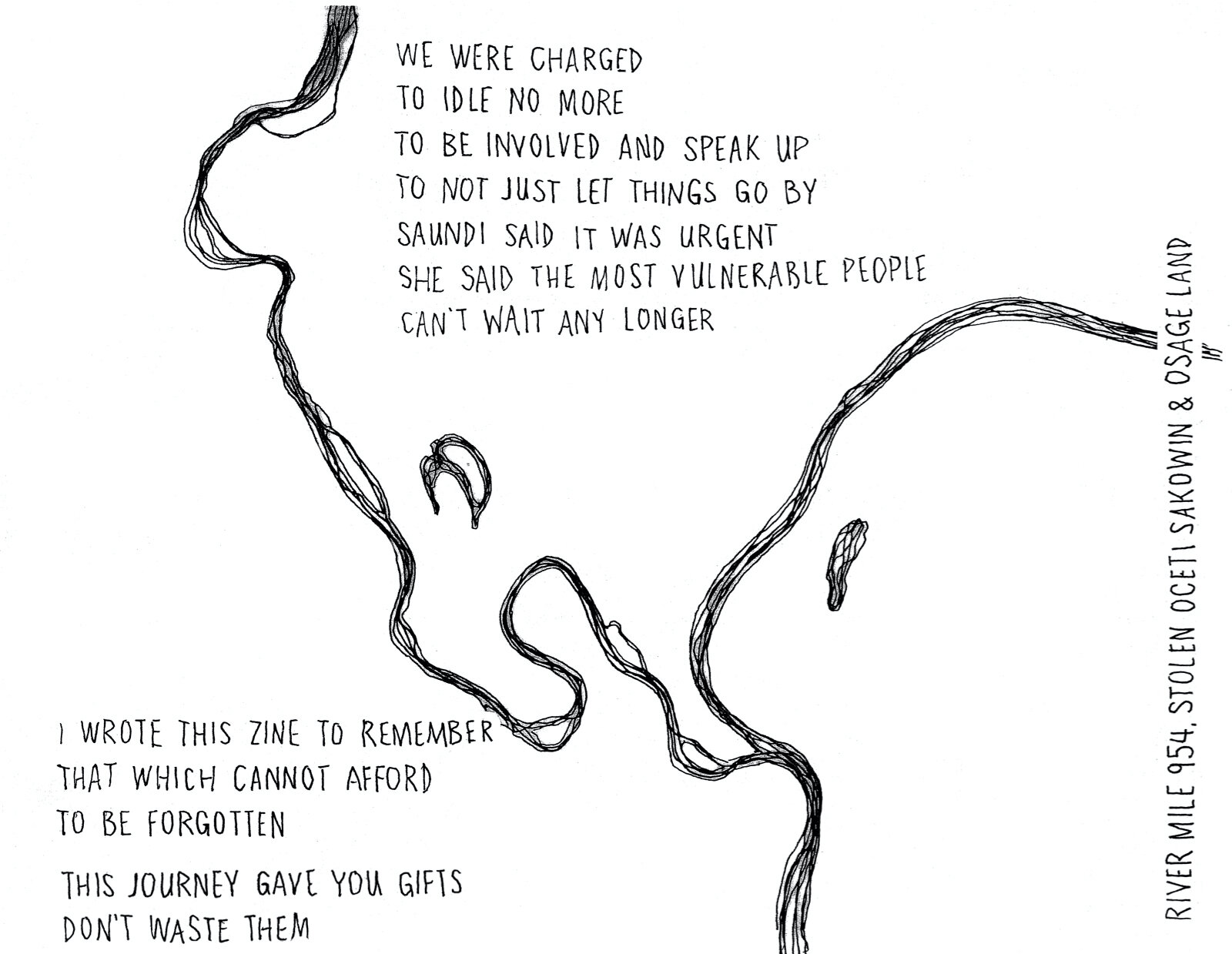

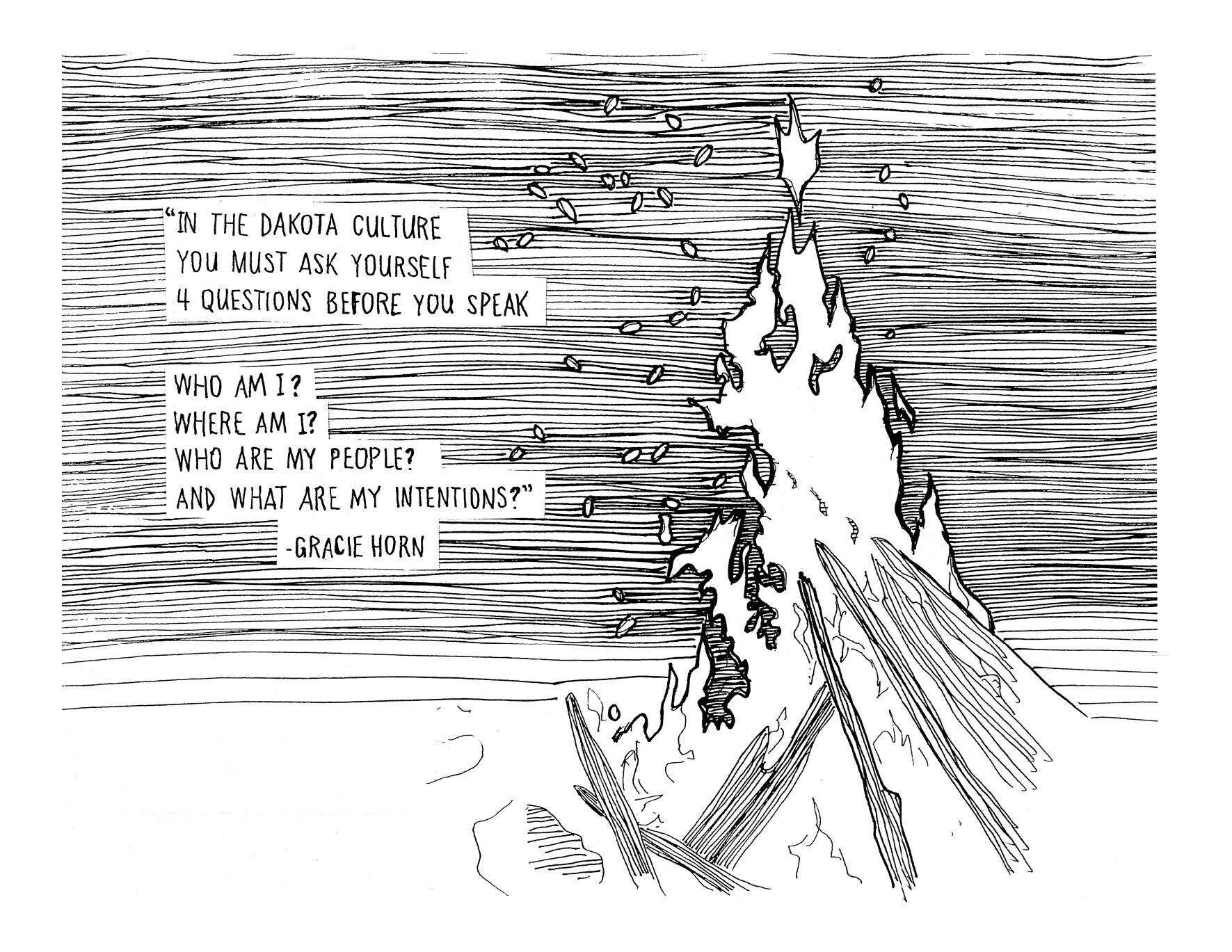

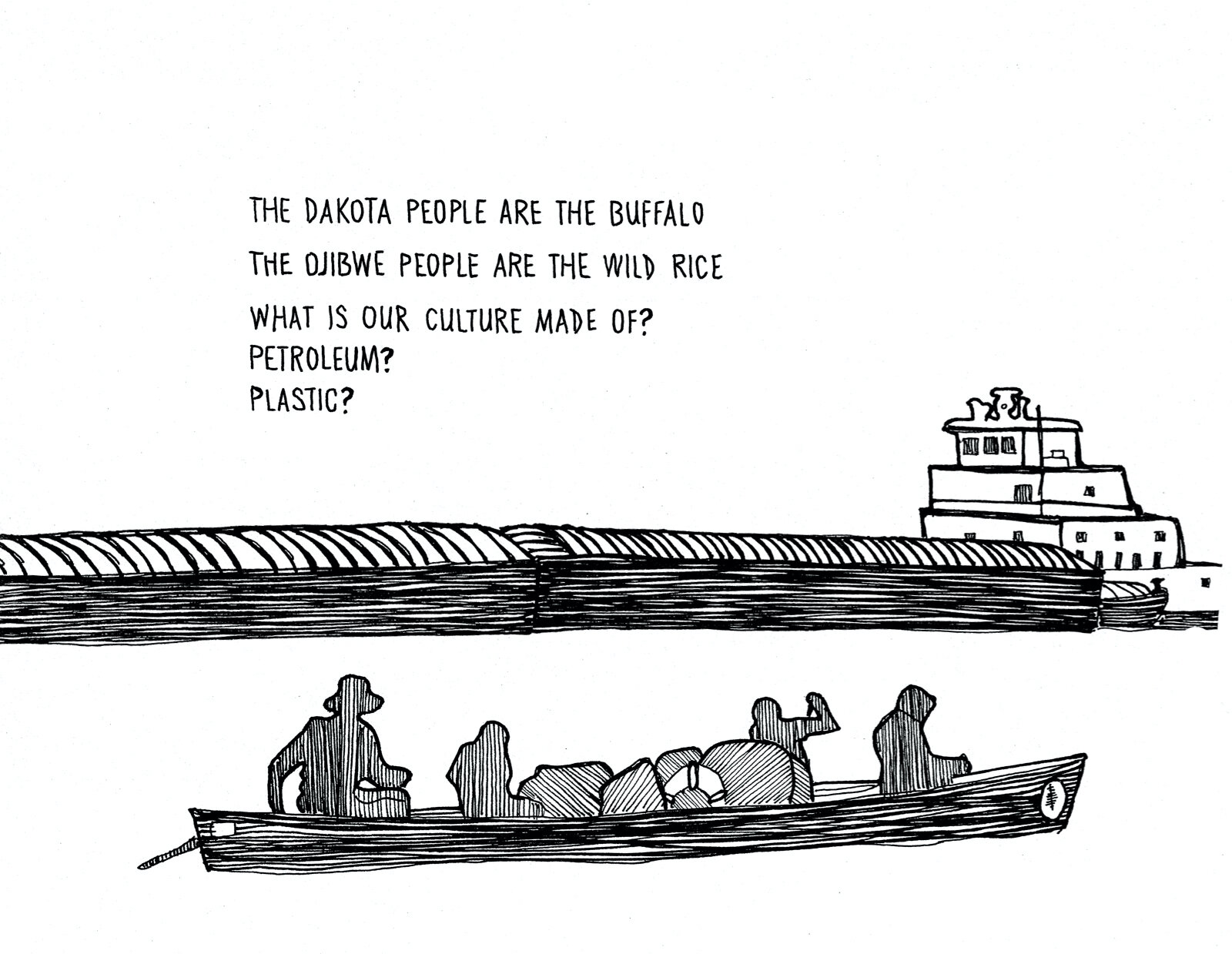

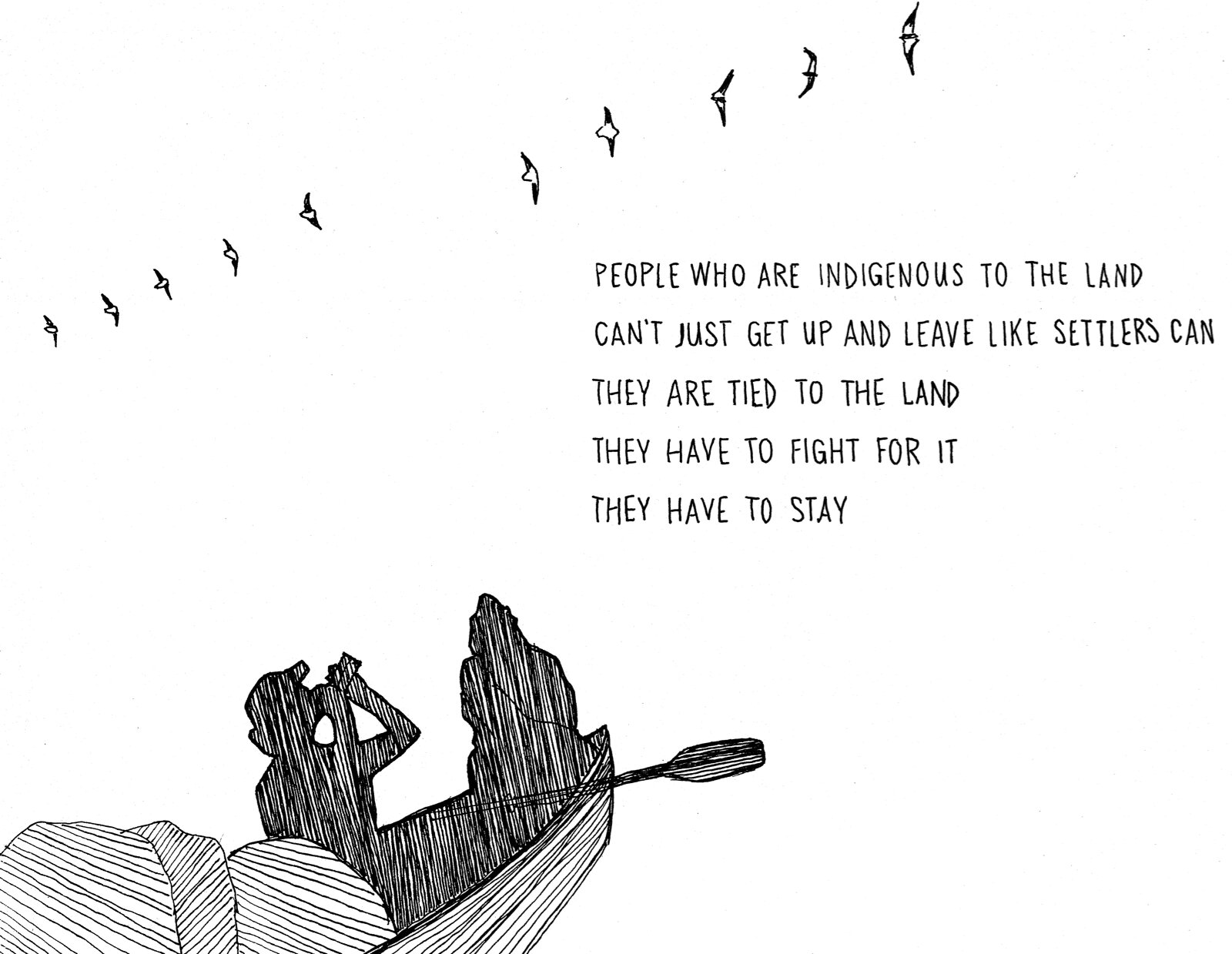

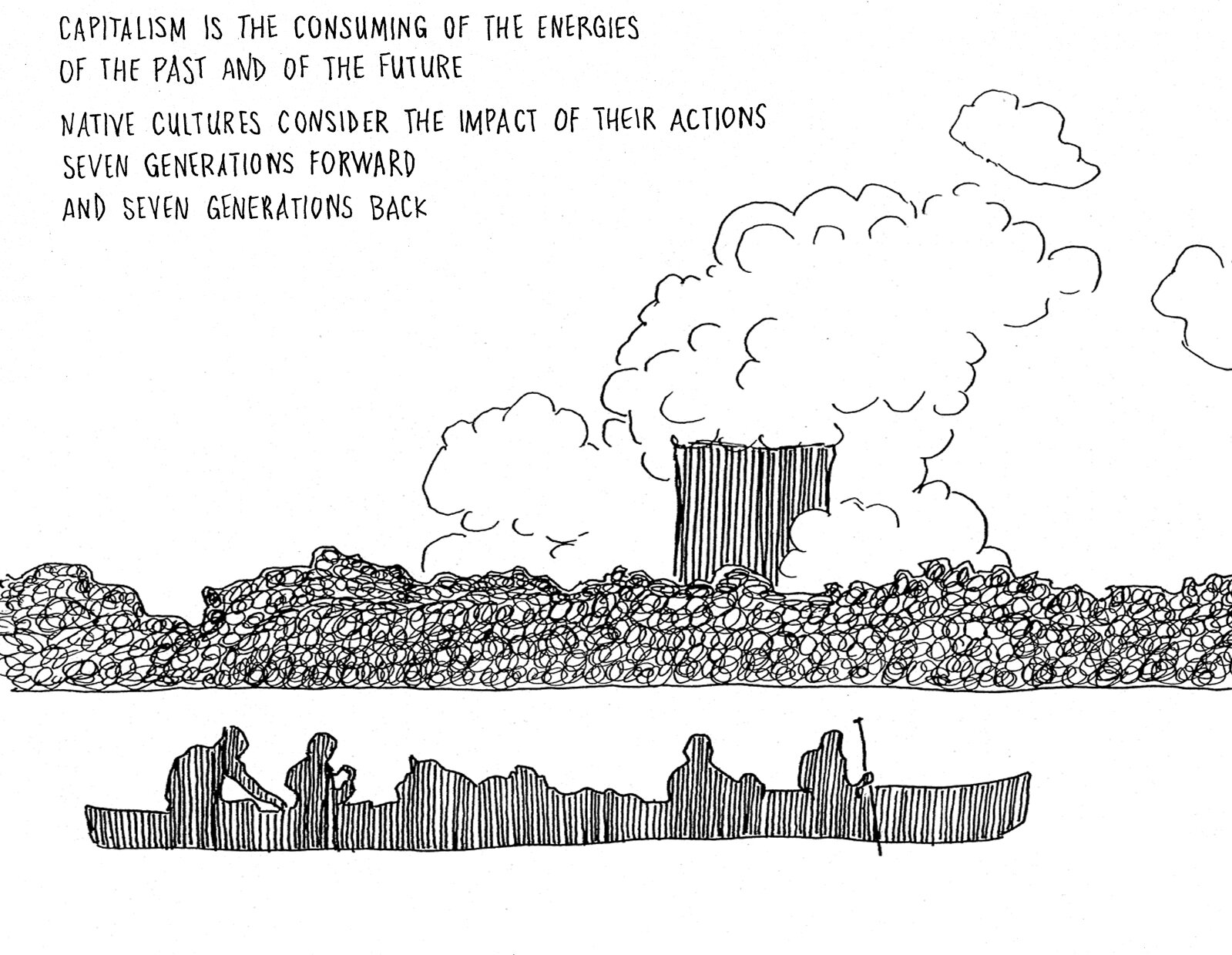

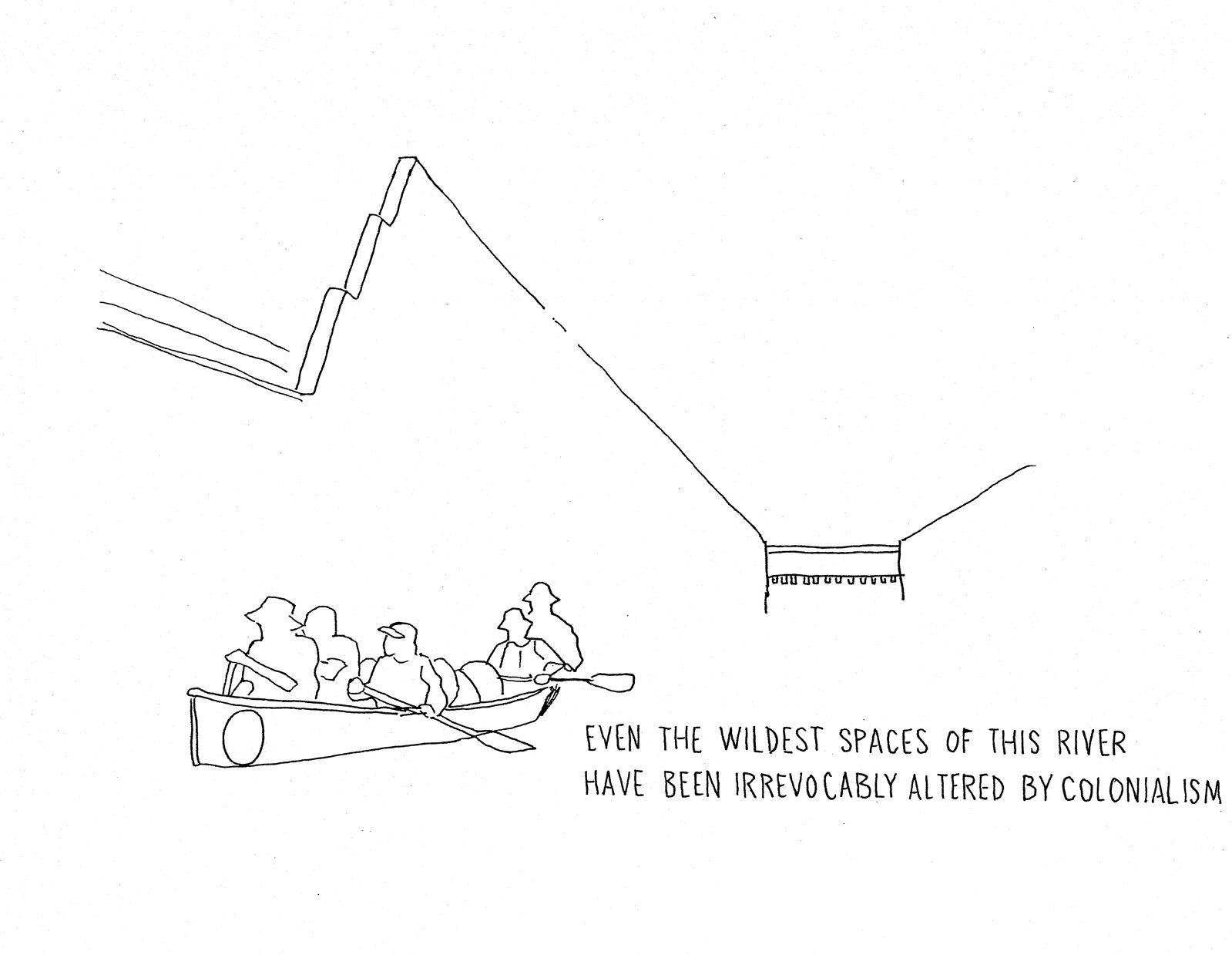

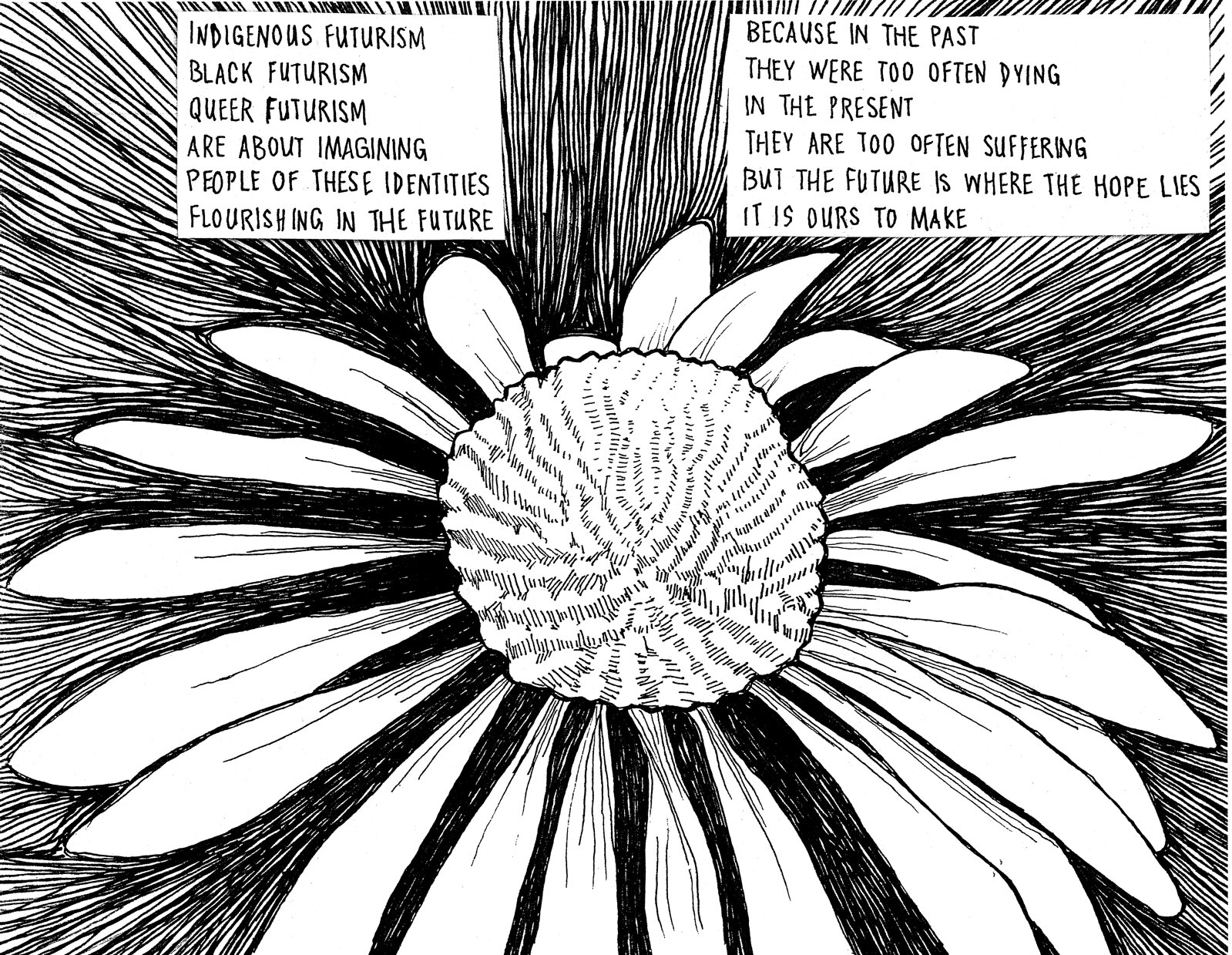

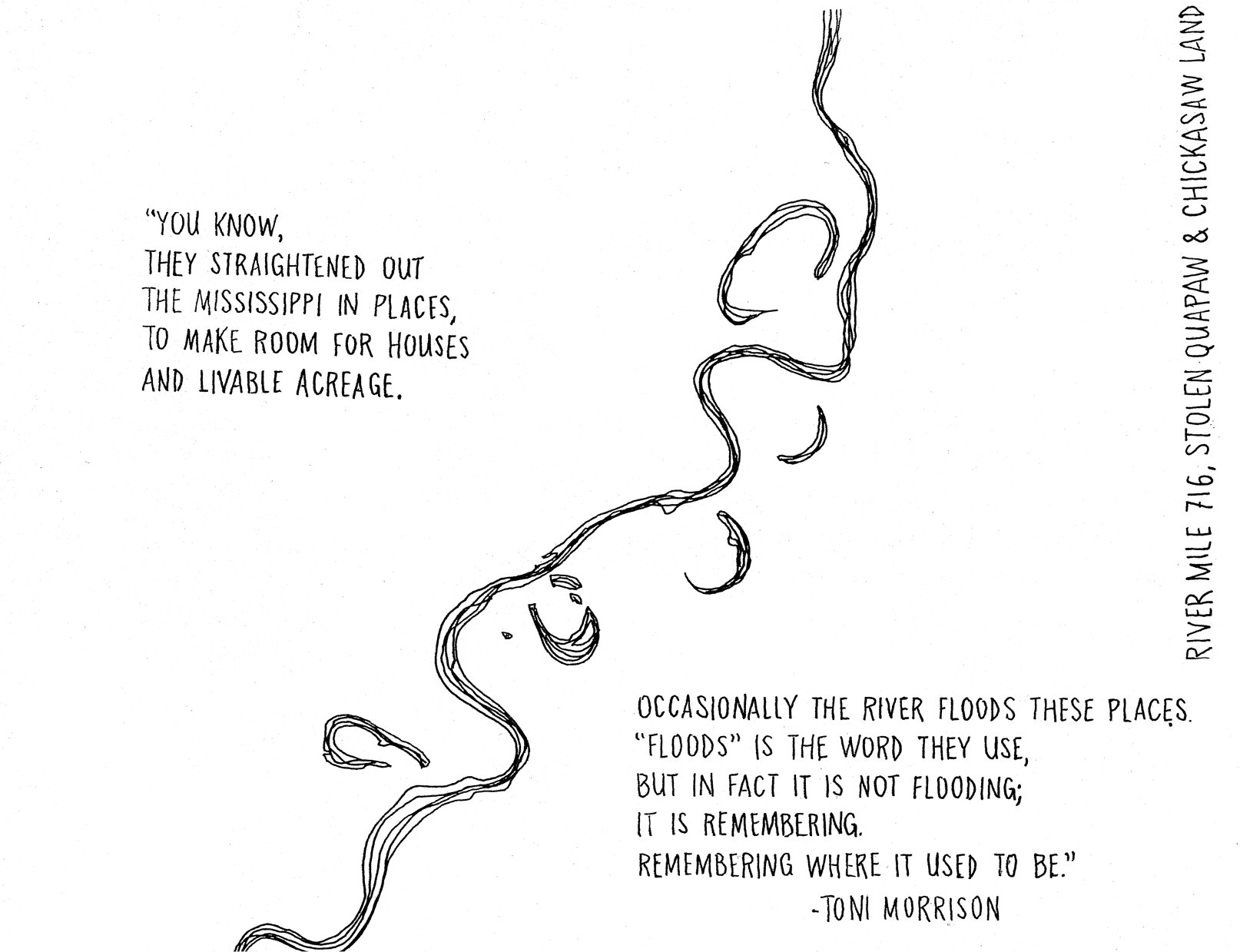

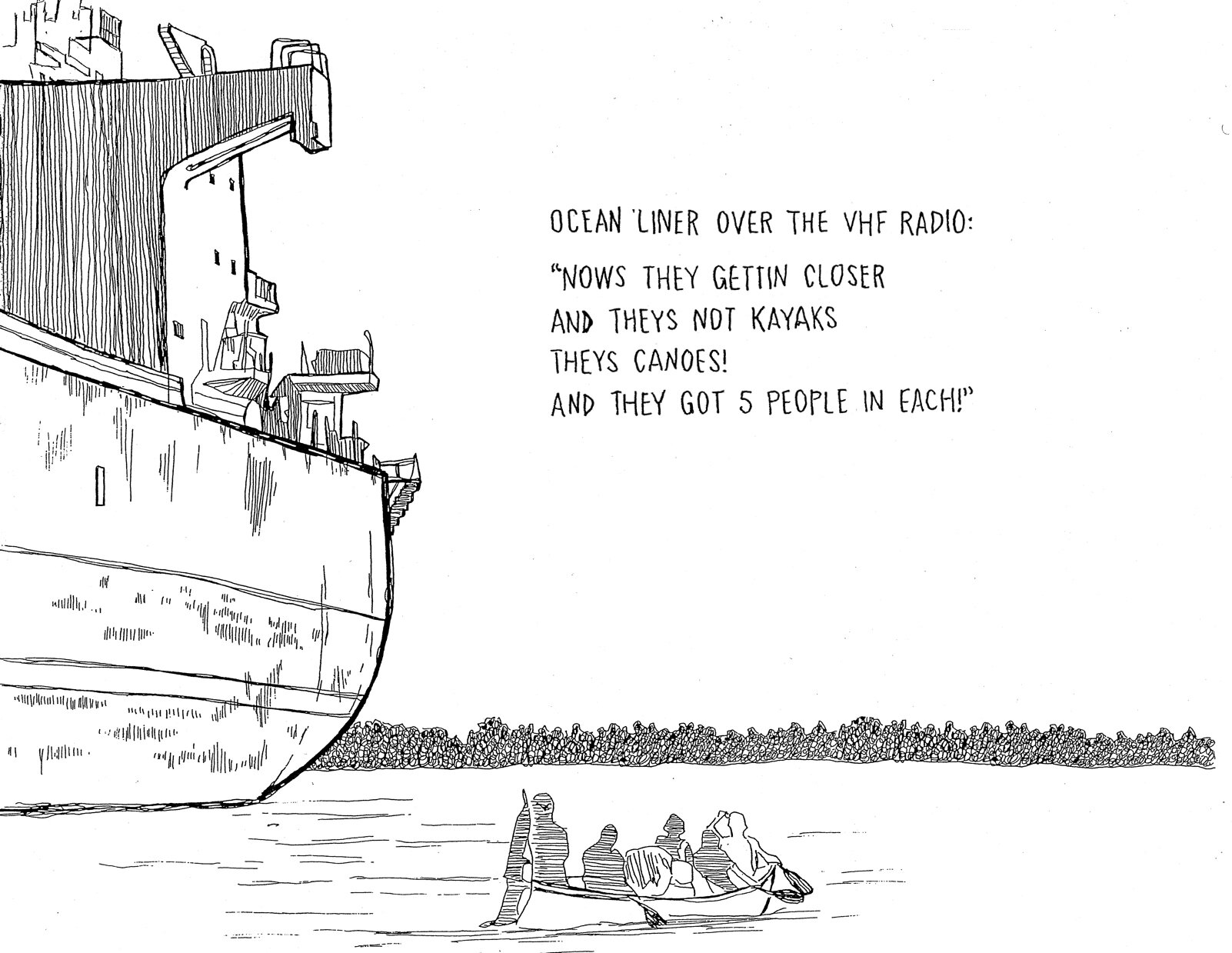

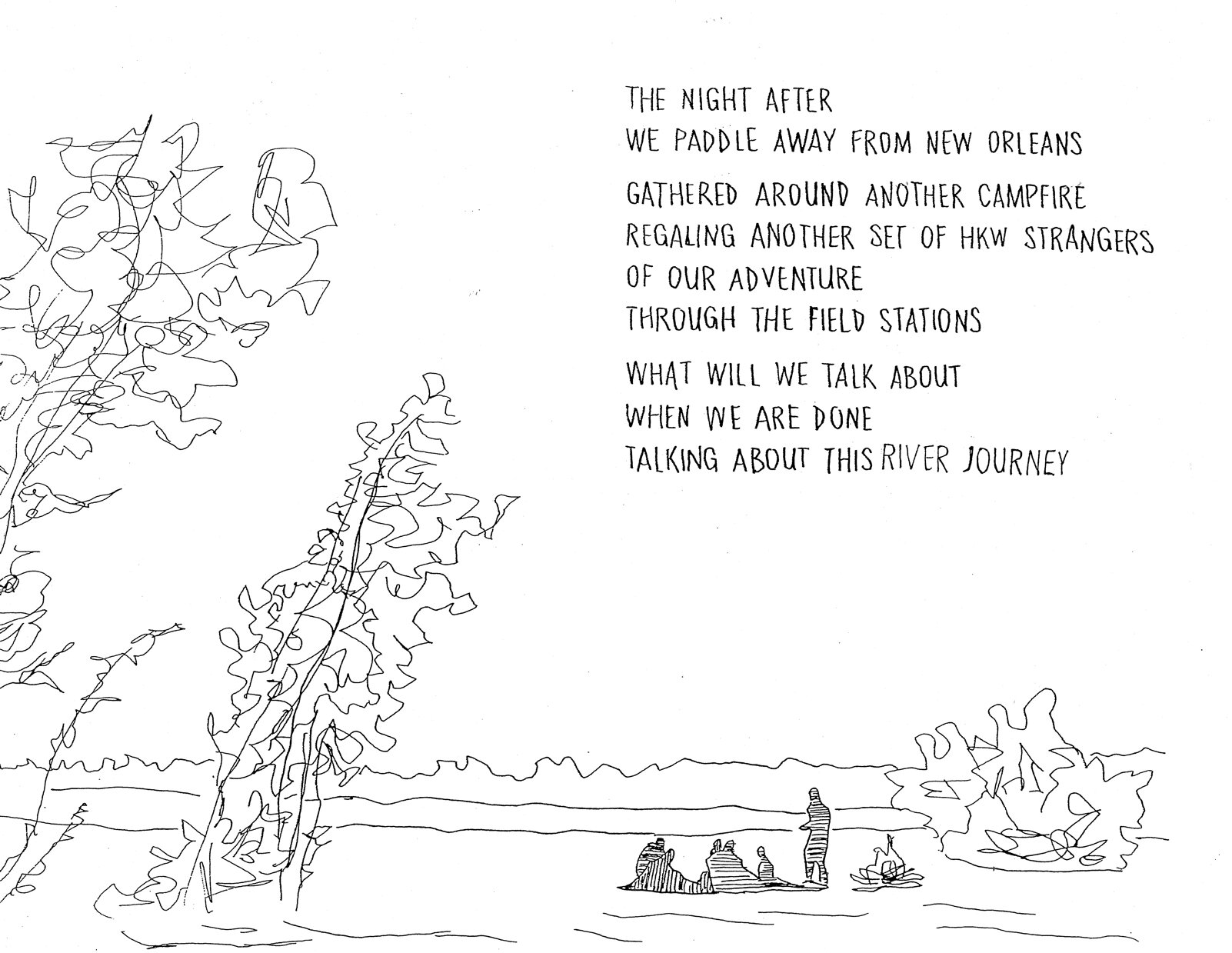

Idle No More

Zine

You explain and explain and clarify

and correct their incorrect pronunciation

and explain

until they remember just how vast your ocean is,

how microscopic your islands look in it,

how easy it is to miss when looking

on a map of the world.

01

Yish Yan

35mm Photograph

The galaxy within the waters of Yosemite National Park. Each year in the late spring and early summer, the clearest, coldest and cleanest waters run through Yosemite as the snow melts down from the Sierra Nevada mountains. This water, which holds the spark of life, faithfully nourishes the forest year after year.

Night Swim (the dark mother)

Erin Oliver

2019

Installation with bubble wrap, glass, and multiple video projections 10’ x 15’ x 6’

Night Swim explores notions of topographical substrata and spatial boundaries, as well as the intricacies of light and water phenomena. Plastic bubble wrap creates a suspended horizon, and hand-shaped glass catches and refracts light from video projections of Florida’s springs and waterways to create an ambiguous yet familiar space.

Undertow

Nancy Kim

Digital Image. Pigment and thread embedded in Acrylic paint skin.

Lewalana II

Poured with a mixture of deep sea equatorial water and coastal waters from Kohanaiki, Hawaiʻi Island, Lewalana II is part of a series of works that imagine the feeling of weightlessness in outer space as akin to the weightlessness of floating in saltwater.

Stained Glass Windows II

Shulamith Nebenzahl Levine

Acrylic on canvas

“In this painting, my mother used her characteristic technique of laying paint thickly on a canvas, and then manipulating the wet paint to create texture. The object she used to manipulate the paint in this case was a children’s stencil of the Hebrew alphabet. By raising a seething seascape of letters out of an inanimate mass of acrylic, my mother re-enacted the Jewish creation story, in which God uses words to call the sea, the land, and the sky into being, as well as the legend of a medieval sage who breathed life into a clay figure by carving in its forehead the word “emet,” or “truth.” This painting celebrated my mother’s power, as a woman and an artist, to breathe life and water into a dry, synthetic materials through the power of her hands and her words.”

—Haninah Levine

Excuses people make

for why they didn’t see it

before.

—“Atlas” (2018)

Terisa Siagatonu

A Song to the Water from a Loving Child

2018 - 2019

Lake Erie shoreline found objects, sand, rock, buckets, water textiles with videoThis piece is the artist's response to this loving child. A moment of hard truth. A moment where we know gratitude is not enough. Water is the lifeline for Dó:so:wë:h, currently known as Buffalo, NY. Since time immemorial, before the arrival of Europeans, through ungrateful industrialization and into today the water, the Great Lakes, her rivers streams and creeks, have sustained this place currently known as Buffalo, NY and many communities along these fresh water lifelines.

Through reservoirs of land theft and projects eagerly backed by the Niagara River Power Authority, to the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway, we witnessed not only the loss of water we could touch, drink, eat from, but thousands of acres of land. Rivers turned to rivers of fire, so toxic they burned. These waters make life possible. And what do we have left to give her but our gratitude and apologies and songs?

All donations to The Chapter House help us curate shows like this one. Please donate today!